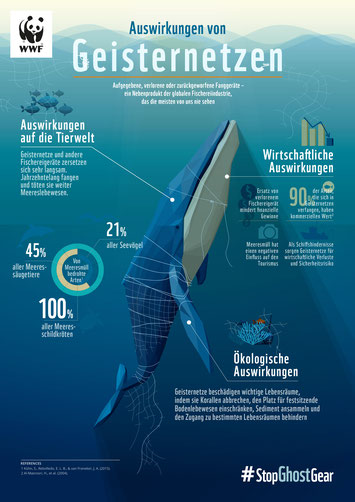

Das geht aus einem neuen Report des WWF hervor. Ganz besonders gefährlich sind verlorengegangene Netze, sogenannte Geisternetze. Sie zersetzen sich nicht nur langsam zu Mikroplastik, sondern sind auch eine tödliche Gefahr für Fische, Meeressäuger, Schildkröten und Vögel, die sich darin verfangen und sterben.

"Wir brauchen wirksame Gesetze und Kontrollen weltweit, damit Netze nicht mehr ins Meer geraten oder dort verbleiben. Außerdem müssen die Regierungen der Küstenstaaten für Bergung und Vorsorgemaßnahmen verantwortlich sein", fordert Jochen Lamp, Leiter des Geisternetz-Projektes beim WWF Deutschland.

Der pazifische Müllstrudel

Wie groß das Problem ist, lässt sich besonders gut im Pazifischen Müllstrudel erkennen. Der riesige Müllstrudel besteht aus 79.000 Tonnen Plastik, fast die Hälfte davon sind Netzteile, Taue oder Angelschnüre. Rund um den Erdball gehen jährlich ein Drittel aller Langleinen und Angelschnüre verloren und allein in den europäischen Meeren verschwinden jedes Jahr mehr als 1.000 km Netze im Wasser - das entspricht der Strecke von den Alpen bis zur Ostsee.

Fischereimüll ist ein großes Problem

"Fischereimüll im Meer ist ein ebenso großes Problem wie Verpackungsmüll. Wir sehen ihn jedoch nicht, weil er meistens unter der Wasseroberfläche treibt oder auf dem Grund des Meeres liegt. Für Meerestiere wie Fische, Delfine, Seevögel oder Robben ist es allerdings die gefährlichste Art von Plastikmüll, weil er dafür gemacht ist, zu fangen. Sie können sich darin verheddern, sich Gliedmaßen abschnüren und qualvoll ersticken oder verhungern", erklärt Andrea Stolte, die das Geisternetzprojekt beim WWF koordiniert.

Gesetze verbieten das Verschmutzen der Meere

Eigentlich verbieten bestehende Gesetze die Verschmutzung der Meere. Auf internationaler Ebene ist die Entsorgung von Fischereigerät auf See sowohl über das UN-Seerechtsübereinkommen als auch durch das MARPOL-Abkommen verboten. Geht ein Netz verloren, sind europäische Fischer zuerst verpflichtet, es selbst zu bergen und ansonsten den Verlust den nationalen Behörden zu melden, die dann für die Bergung zuständig sind. "Diese Gesetze sind leider nur effektiv, wenn ihre Einhaltung auch kontrolliert wird. Das ist auf internationaler Ebene auf den Meeren kaum möglich, dafür fehlt es schlichtweg an Mitteln und politischem Willen. Das globale Problem der Verschmutzung durch Geisternetze lässt sich nur lösen, wenn die einzelnen Küstenstaaten ihre Verantwortlichkeit dafür endlich übernehmen. Kontrolle, Bergung und Vorsorge müssen also staatliche Aufgabe bzw. Ländersache werden", erklärt Jochen Lamp.

Finanzierung mit Spendengeldern

Bisher übernehmen in vielen Ländern Umweltschutzorganisationen das Bergen der Netze, finanziert wird es häufig aus Spendengeldern. Auch der WWF hat in den letzten sechs Jahren 18 Tonnen Geisternetze aus der Ostsee geborgen. In Deutschland sind die Küstenländer Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Niedersachsen und Schleswig-Holstein schon auf einem guten Weg.

Bergung der Netze muss verpflichtend werden

Trotzdem sieht Lamp weiteren Handlungsbedarf und schlägt einen Dreiklang aus Maßnahmen vor. "Der WWF fordert, dass die Bergung der Netze generell verpflichtend wird. Zurzeit ist das nur nötig, wenn die Sicherheit von Seeschifffahrtsstraßen gefährdet ist. Die schädliche Wirkung auf die Umwelt bleibt außen vor. Zudem müssen klare Verantwortlichkeiten bei den Behörden geschaffen werden, damit eindeutig ist, wer die Bergung vornehmen muss. Als dritten Punkt setzt sich der WWF für die Absicherung der Fischer ein. Sie verlieren die teuren Netze nicht freiwillig. Eine Fischerei ganz ohne Netzverluste durch Unfälle ist leider kaum vorstellbar. Solange sie allerdings mit der Bergung alleingelassen oder teuer zur Kasse gebeten werden, ist die Bereitschaft, ein verlorengegangenes Netz zu melden, gering." Der WWF schlägt deshalb vor, Mittel aus dem Europäischen Fischereifonds zur Finanzierung der Bergung zu nutzen und so die Meldequote zu erhöhen, damit verlorene Netze gar nicht erst so lange im Meer liegenbleiben, dass sie zur Gefahr für Menschen und Tiere werden.

pm, ots

Bildrechte: WWF Deutschland Fotograf: WWF World Wide Fund For Nature

English version

Plastic in the sea is associated with floating packages or discarded plastic bottles. But at least one third of the world's plastic waste in the oceans consists of fishing gear such as nets and ropes, and around one million tons are added each year. This is the result of a new report by the WWF. Particularly dangerous are lost nets, so-called ghost nets. Not only do they decompose slowly into microplastics, but they are also a deadly danger for fish, marine mammals, turtles and birds that get caught in them and die.

"We need effective laws and controls worldwide to ensure that nets no longer end up in the sea or remain there. In addition, the governments of coastal states must be responsible for salvage and precautionary measures," demands Jochen Lamp, head of the ghost net project at WWF Germany.

The Pacific garbage maelstrom

How big the problem is can be seen particularly well in the Pacific garbage maelstrom. The huge trash whirlpool consists of 79,000 tons of plastic, almost half of which are power packs, ropes or fishing lines. Around the globe, one third of all longlines and fishing lines are lost every year, and in the European seas alone, more than 1,000 km of nets disappear into the water every year - the equivalent of the distance from the Alps to the Baltic Sea.

Fishing waste is a major problem

"Fishing waste in the sea is as big a problem as packaging waste. However, we do not see it because it usually floats under the surface of the water or lies on the bottom of the sea. For marine animals such as fish, dolphins, seabirds or seals, however, it is the most dangerous type of plastic waste because it is made to catch. They can get tangled up in it, string off limbs and suffocate or starve to death in agony," explains Andrea Stolte, who coordinates the ghost net project at WWF.

Laws prohibit the pollution of the seas

Actually, existing laws prohibit the pollution of the seas. On an international level, the disposal of fishing gear at sea is prohibited by both the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the MARPOL Convention. If a net is lost, European fishermen are first obliged to salvage it themselves and otherwise report the loss to the national authorities, who are then responsible for recovery. "Unfortunately, these laws are only effective if compliance is monitored. This is hardly possible at international level on the seas, there is simply a lack of resources and political will. The global problem of pollution by ghost nets can only be solved if the individual coastal states finally take responsibility for it. Control, salvage and prevention must therefore become a state task or a national responsibility," explains Jochen Lamp.

Financing with donations

In many countries, environmental protection organizations have been responsible for recovering the nets, often financed by donations. The WWF has also recovered 18 tons of ghost nets from the Baltic Sea in the last six years. In Germany, the coastal states of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein are already on the right track.

Recovery of the nets must become mandatory

Nevertheless, Lamp sees further need for action and proposes a triad of measures. "The WWF is calling for the recovery of the nets to become generally mandatory. At present, this is only necessary if the safety of maritime shipping lanes is endangered. The harmful effect on the environment is not taken into account. In addition, clear responsibilities must be established with the authorities so that it is clear who has to carry out the salvage. As a third point, the WWF is committed to ensuring the safety of fishermen. They will not voluntarily lose the expensive nets. Unfortunately, fishing without any net losses due to accidents is hardly conceivable. However, as long as they are left alone with the recovery or are asked to pay for it expensively, the willingness to report a lost net is low". The WWF therefore proposes to use funds from the European Fisheries Fund to finance the recovery and thus increase the reporting rate so that lost nets do not remain in the sea for so long that they become a danger to humans and animals. pm, ots, mei